Copy editors start with spelling and grammar, and they don’t stop until every page has perfect style, structure, clarity, and tone.

You probably think of copyediting as quality control. And while that’s not exactly wrong, it doesn’t capture the full scope of what copy editors do. In fact, what most people think of as copyediting—catching typos—is actually proofreading (not that there isn’t some overlap; typos crop up at every stage).

If the purpose of writing is to communicate something to an audience, its success is measured not by whether the language is “correct,” but by how effectively, efficiently, and elegantly it achieves that goal. Multiple considerations come to bear on that. For the sake of expediency, I’ll group them into three broad categories, which I present here in order of increasing precedence.¹

3. Convention

Just because nothing is objectively “right” or “wrong” in language doesn’t mean there are no useful conventions. Language only works when we collectively agree on its meaning, so it’s to your advantage to swim with the proverbial current, using words the way most people use them and spelling them the way most people spell them. Not because you’ll go to Grammar Jail if you don’t, but because it makes for better communication.

It’s not just a question of decipherability, either. Even when departures from convention are intelligible, they can still be distracting. So yes, copy editors fix spelling mistakes, grammatical mistakes, and syntactical mistakes, and amend idioms that are incorrectly phrased or used in the wrong context. You can call it “correcting” the language if you like, but it’s more accurate to say that it’s conforming the language to a particular convention, to the reader’s expectations, and to their probable understanding.

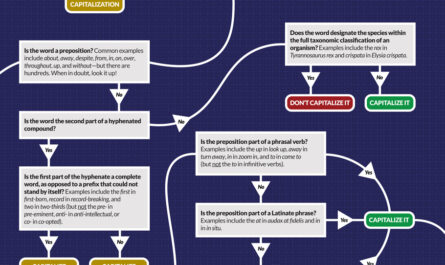

The publishing industry also has its own conventions—conventions that govern style rather than content, like the rules against starting a sentence with a numeral, or ending a column with the first half of a hyphenated word and beginning the next column with its second half.

Fortunately, these kinds of things are usually pretty easy to look up. You can google idioms and questions of grammar. Every publication uses a single dictionary and style manual as its primary references. And anything not included therein will (ideally) be addressed in the publication’s own style guide. To wit:

2. Consistency

Where matters of convention are up for discussion—whether or not to use a serial comma, whether a terminal ellipsis should have three periods or four, whether it’s spelled “cafe” or “café,” and so on—house style takes over. It’s convention of a more idiosyncratic kind, in that it keeps a publication’s peculiar elements consistent each time they appear.

But house style goes far beyond questions of spelling and grammar. There are no universally accepted answers to most of a publication’s style choices. Copy edits for style are typically made only after a story has been laid out, which allows an editor to see not just the story but everything that appears on the page with it, including images and captions, page numbers, and so on. Even these elements demand consistency. If you use open en dashes on page 14 and closed ems on page 27, for example, it comes across as sloppy and unprofessional, which casts your entire publication in a dubious light.

Where do page numbers go? Do heds follow headline case or sentence case? Is the “by” in a byline capitalized? Do gutter credits end in a period? Do deks? Are foreign currencies specified before or after the sum? Is ten plus two “twelve” or “12”? Is it “Number 5,” “No. 5,” “№ 5,” or (God forbid) “#5”? Should it be “P.D. James” or “P. D. James”? Should drop caps include an opening quotation mark or apostrophe? How do you combine hanging dashes and quotes? How many words are styled as lead-in text? Can we say “kg,” or does it have to be “kilograms” every time? Are there quotation marks around pull quotes? Are the names of podcasts italicized or not? Do lists use bullets or numerals? Arabic or Roman?

Every publication requires hundreds of style decisions like these. The answers vary from publication to publication and may even override convention. (The New Yorker, for instance, frequently [and consistently] eschews custom for its preferred spelling of words like “teen-ager” and “coördinate”; it may be dancing to the beat of its own drummer, but at least it’s keeping time.)

A copy editor does not typically make these decisions alone; they either follow an established house style or they develop a new one in conversation with the editorial team. But once these decisions have been made, it’s the copy editor’s job to enforce them and keep the elements of style uniform from page to page and issue to issue. Marking up these style changes can constitute half the copy editor’s job.

Consistency is important not only to help a publication establish its trustworthiness and authority, but also to help the reader understand what they’re looking at. Which brings us to the copy editor’s most important consideration: reader comprehension.

1. Clarity

All of the above is ultimately in service to the copy editor’s overarching goal of making everything as clear as possible. That almost always means following convention and maintaining consistent house style. Almost always. But the rules are here to serve us, not the other way around. If breaking the rules helps get the point across more effectively, efficiently, or elegantly, that option should remain on the table. (Even those publications that officially forsake the serial comma, for instance, will often resort to it if it means avoiding the intolerable.) If you do decide to bend the rules, please, please be sure it’s worth the potential consequences—both the aforementioned loss of credibility and the hate mail it will garner.

But for all the times this will come up in a copy editor’s career, it isn’t worth dwelling on (I may have intentionally broken the rules twice ever). No, the copy editor’s fixation on clarity is primarily focused on the structure of the language itself—not so much whether it’s grammatical (which we should take as given) but whether its meaning is unmistakable. And concise! Precision needn’t come at the cost of brevity.

Angela vehemently denied Karen’s claim that she’d been involved from the very beginning.

Who was allegedly involved from the beginning—Angela or Karen?

Audi’s latest lineup of all-electric vehicles features a jaw-dropping array of state-of-the-art features.

So, it features features?

She swept onto the scene with aplomb, utilizing her wiles and experience to rally her team and build confidence.

“Utilize” is one of those words that everyone understands but almost nobody uses correctly; when it’s added to make a writer sound smart, it quite often achieves the opposite result. “Utilize” and “use” are almost (but not quite) close enough to achieve true synonymity, and so should be used with caution. Ditto pairs like “compose” and “comprise,” “intent” and “intention,” “contrary” and “contradictory”—the list goes on.²

It’s been seven months since I, in an attempt to distract myself from the sense of loss I felt after the death of my beloved pet, took up knitting.

Is there any good reason to place this sentence’s subject and verb so far apart? Could you say “It’s been seven months since I took up knitting in an attempt to distract myself from the sense of loss I felt after the death of my beloved pet” instead?

But, knowing Ed, the pilot from Abilene, Texas, was not, for the moment, in the building, I turned to Frank instead.

Perfectly grammatical, and perfectly awful. This represents an extreme case of comma-itis, but even healthy sentences may show symptoms.

Ireland is a country famous for its rolling green hills, whiskey distilleries, and ancient castles that is also known for its hospitality.

Long sentences often sound better when they’re broken up into two shorter ones. Some not-so-long sentences do too: “Ireland is famous for its rolling green hills, whiskey distilleries, and ancient castles. It’s also known for its hospitality.”

He left his clients with nothing, and many of them were driven to acts of desperation as a result.

Especially if this is the final sentence of a paragraph or section, “as a result” is a pretty weak note to end on—it goes out with more of a fizzle than a bang. Its meaning is identical, but “Because he left his clients with nothing, many of them were driven to acts of desperation” lands on the word that packs the most punch.

Even though, on arriving at the bustling station and having my luggage deposited before me, I’d been inclined to accept the proposal that Cline had graciously made before I climbed aboard that streaking black train to Hollyoaks, by the time I was deposited before the hotel door by my taxi, I’d resolved to decline it, so capricious was the state of my usually transigent mind at that time.

The sentence above contains no spelling mistakes or grammatical errors that I’m aware of. But could it be better?

Editing individual sentences without changing the story’s overall structure is called “line editing,” and while it officially falls under the purview of a story’s handling editor, it’s more of a co-parenting situation than sole custody. At this level, copyediting goes above and beyond corrections to spelling, grammar, and even style to focus on the deeper issues of the text’s content—what it’s trying to say and whether that message comes across as intended. At its best, it achieves all this without detracting from the original author’s unique voice.

Nuance plays a much larger role in line editing. Copy editors are typically welcome—nay, expected—nay, required—to suggest ways that poorly written sentences like the ones above can be improved, especially when clarity is at stake. Note that I said “suggest”; there may be scenarios where a publication’s copy chief wields final say, but in my experience, a copy editor can only advocate for changes that the handling editor will then accept or reject.

Depending on the situation, a handling editor may also be open to a copy editor’s suggestions for more substantive changes: cutting paragraphs that repeat information or are tangential to the article’s primary thesis, adding section breaks or reordering sections to present ideas in a more logical way, flagging sections where more information or supporting quotations are needed, and so on. These types of edits can alter a story’s overall structure—they’re not to be made lightly—but because they’re only suggestions, it often behooves the copy editor to raise them.

While a copy editor’s changes can range from the minuscule to the transformative, the ultimate goal of each remains the same. I repeat myself, but the best writing is effective (in that it accurately conveys the ideas the writer intends to convey), efficient (in that it does so in as few words as necessary), and elegant, and the best copy editors won’t let anything go to press until it’s all three. In saying this, I risk veering from wholesome self-promotion into vulgar self-aggrandizement, but that is the bar we aim for.